from Special Operations

from Special Operations |

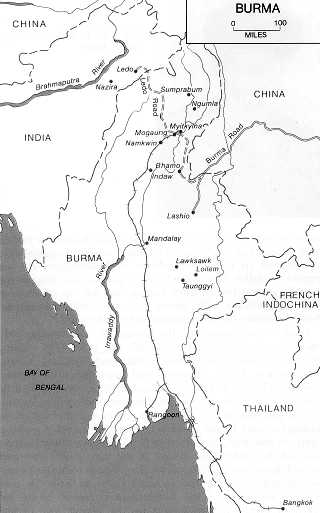

Lacking men, equipment, funds, a clear directive from Washington, and current intelligence on the situation in Burma, Eifler faced an immense task in building a clandestine organization. Although the unit successfully resisted minor staff assignments from the overworked CBI Theater headquarters, it still had only twenty men. Since American agents in Burma would attract attention, the detachment canvassed the British-led Burma Army for Anglo-Burmese volunteers. Supplies and equipment were a more difficult. Communications would be critical to operations; yet the radios available in the Pacific theater were woefully inadequate in range and adaptability to the damp Burmese climate. Funds were so tight that Eifler paid for many of the detachment's initial expenses out of his own pocket. Finally, a Japanese air raid destroyed the detachment's warehouse, aggravating an already grim supply situation.

At a tea plantation near Nazira in the northeastern Indian province of Assam, the detachment established a base camp under the guise of a center for malarial research. Using the services of a former district forester in Burma, Detachment 101 recruiters found about fifty refugees and Burmese military personnel

|

In early February 1943 Group A, now consisting of twelve Anglo-Burmese agents under Capt. Jack Barnard of the Burma Army, parachuted into the Kaukkwe Valley of central Burma. The team was supposed to cut the Mogaung-Katha Railroad in conjunction with an Allied offensive and then organize guerrillas south of Myitkyina. ... The success of the initial operation was partially obscured by the complete failure of two missions that followed....Despite the two setbacks, Stilwell was impressed with the results of the initial missions and approved an expansion of Detachment 101's strength and activities. By the end of January the detachment, largely through use of the "jungle grapevine," was already providing Stilwell's headquarters with valuable intelligence on developments behind Japanese lines. The American theater commander directed Eifler to expand his contacts with the Kachin natives, to gather more information, and ultimately to provide the Kachins with arms and equipment for guerrilla operations against the Japanese. The focus of Detachment 101's activities was changing from sabotage to guerrilla warfare.

In February Capt. William C. Wilkinson and four agents arrived in Sumprabum and began to contact Kachins in the area. A Japanese advance on the town soon forced them to flee, but in April Wilkinson, operating from Fort Hertz, infiltrated Japanese lines by foot to establish an operating base at Ngumla, where he raised a small guerrilla force, harassed the Japanese, and gathered intelligence from as far south as Mandelay.

|

West of Myitkyina, Vincent Curl, now a second lieutenant and proud owner of a magnificent flowing auburn beard, formed a small guerrilla army in the steep mountains near Naubum. In early March 1943 Eifler had sent three groups of agents into the upper Hukawng and Taro valleys to reconnoiter the area between Japanese patrols and the engineers who were constructing the Ledo Road. One month later Curl received command of the consolidated groups, jokingly code named KNOTHEAD after he misplayed a pop fly in a unit baseball game. Infiltrating through enemy lines from Fort Hertz, Curl crossed the Kumon Range into the Hukawng Valley, where he joined Zhing Htaw Naw, a Kachin leader who had been fighting his own guerrilla war against the Japanese. Zhing Htaw Naw would serve as combat leader and supply the soldiers and guides, while Curl agreed to provide equipment, supplies, and overall coordination. Assisted by KNOTHEAD, the Kachins gathered information, harassed Japanese detachments, provided targets for the Tenth U.S. Air Force, aided downed Allied flyers, and even constructed a makeshift airstrip, which they camouflaged with movable huts when not in use. By February 1944 Curl's group had helped to assemble about 600 guerrillas.

Despite vastly different cultural backgrounds, Kachins and Americans, on the whole, got along quite well. Although the members of Detachment 101 found the local diet barely palatable and were repelled by the Kachin practice of collecting the ears of the dead, they appreciated the courage, loyalty, and honesty of the tribesmen. When a payroll bag containing $500,000 in rupees ruptured in a supply drop, for example, local natives returned all but $300 of the missing money.

|

The Americans found the Kachins to be natural guerrilla fighters. They showed great care in the planning and preparation of an ambush, particularly in their use of the pungyi stick, a smoke-hardened bamboo stake of one to two feet in length. In preparing an ambush, the Kachins camouflaged the site to appear as natural as possible, placed their automatic weapons to rake the trail, and planted pungyis in the foliage alongside the path. Once the Japanese entered the area, the fire of the automatic weapons drove the surprised enemy troops into the undergrowth, where they impaled themselves on the pungyis. Having inflicted losses, the lightly armed Kachins usually left the area quickly, avoiding prolonged engagements. In contrast, the Americans often displayed too much readiness to stand and fight, not recognizing a guerrilla's responsibility to minimize his own casualties while maximizing those of the enemy.

|

|

The Kachins proved their value in a number of other ways. While Kachin agents initially estimated enemy numbers at roughly three times their actual strength, intensified training gradually resulted in extremely accurate reports. The Japanese skillfully used the dense jungle foliage of Burma to keep their movements and key installations invisible from the air. Consequently, the Tenth Air Force relied heavily on the detachment sponsored guerrillas to find targets and evaluate air strikes. On one occasion, the detachment, carefully examining photographs from the diary of a Japanese pilot captured by the Kachins, discovered that the enemy at a particular airfield were hiding planes in holes covered with sod. It was thus able to pinpoint targets at the seemingly vacant installation. By late 1944 the Tenth Air Force was acquiring 80 percent of its bombing targets from detachment reports. In addition, the morale of Allied airmen flying over the northern Burmese mountains to China improved markedly as OSS teams and agents rescued downed crews and brought them back to friendly lines. In all, Detachment 101 rescued about 400 Allied flyers.

As theater headquarters and the Air Force became more aware of the value of the detachment's operations, the group found it easier to obtain supplies, equipment, and other support. In the detachment's early days, it had been forced to beg or bargain for

|

By the end of 1943 the growth of the detachment and preparations for the coming Allied offensive made necessary a major reorganization. In December Donovan visited and assessed Detachment l0l's progress, even flying in one of the unit's liaison planes to an operating base behind enemy lines. While at Nazira, he decided that Eifler must be replaced. Already prone to rages, the burly colonel had been plagued with severe headaches ever since he had struck his head against a rock while landing the ill-fated Sandoway party. In the ensuing shakeup, Coughlin received command, under Miles, of all OSS activities in Asia. Peers, formerly the operations and training officer of the detachment, took over the command, which was reorganized to encompass the entire scope of OSS activities, including psychological operations and research and analysis. Donovan also promised more resources, for Stilwell was about to direct an increase in the detachment's partisan force to 3,000 guerrillas. To ensure better coordination of the unit's expanded operations, Peers created four area commands and arranged for his operations section to travel with Stilwell's field headquarters in the forthcoming drive on Myitkyina, the key to the Japanese position in northern Burma.

GALAHAD

|

When the new unit assembled, it proved to be a far cry from the elite formation of picked troops that Marshall had envisioned. Despite the best efforts of recruiters in the South and Southwest Pacific, the Caribbean, and the continental United States, few jungle veterans showed any inclination to volunteer for an unspecified "hazardous" mission, and many of those who did suffered from malaria. In a number of cases, commanders seized the opportunity to unload personnel who, for various reasons, did not fit in with their units; when the troops from the Caribbean and the United States gathered at San Francisco, one officer remarked, "We've got the misfits of half the divisions in the country."

Initially, the men of the new unit, code named GALAHAD, had little information on their destination or mission. Although no official word had been issued, rumors had circulated to the effect that the unit would be withdrawn from action after an unspecified operation of about three months' duration. Under the temporary command of Col. Charles N. Hunter, a dour professional who had been an instructor at the Infantry School, two battalions departed San Francisco in mid-September. Enroute to the Orient, they added a battalion from the Pacific areas, bringing the total strength to about 3,000 men.

Arriving in Bombay, India, on 31 October, the GALAHAD troops trained in long-range penetration tactics under Wingate's direction. At Deolali, 125 miles outside Bombay, the troops endured both physical conditioning and close-order drill. After moving to Deogarh in central India, they received instruction in scouting and patrolling, stream crossings, weapons, demolitions, camouflage, small-unit attacks on entrenchments, evacuation of wounded, and the novel technique of supply by airdrop. In December GALAHAD conducted a weeklong maneuver with the Chindits. From the beginning, the unit was hard to handle; when it moved by rail from Deogarh to the Ledo area, for example, one officer found his men shooting out the windows at Indians as if they were riding through the Wild West in the 1870s. Nevertheless, for all its disciplinary problems and Hunter's belief that it needed more training, theater headquarters decided that GALAHAD would be ready for combat by February 1944.

|

On the eve of GALAHAD'S debut on the battlefield the unit found that it would not operate under Wingate. Determined that the only U.S. combat troops in the theater would not serve under a British officer, Stilwell had prevailed on Mountbatten, chief of the new Southeast Asia Command, to place GALAHAD under his control. To command GALAHAD, Stilwell chose one of his intimates, Brig. Gen. Frank D. Merrill, leading American correspondents to dub the unit "Merrill's Marauders." In contrast to Wingate's concept, the two American generals envisioned GALAHAD'S proper role as strategic cavalry, conducting envelopments deep into the Japanese rear while Stilwell's two Chinese divisions advanced on the enemy's front. Their opponent was the veteran Japanese 18th Division, which had conquered Singapore.

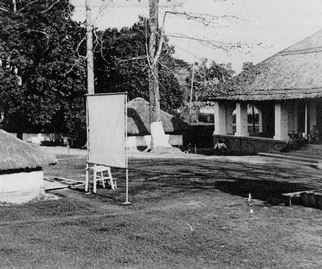

After a 140-mile march from the Ledo area to their jumpoff point near Shingbwiyang, the Marauders enveloped the right flank of the 18th Division. Screened by three intelligence and reconnaissance platoons and supplied by air drops in the infrequent jungle clearings, the three battalions followed obscure trails to a pair of positions near Walawbum, astride the expected Japanese line of retreat. The Chinese division commanders, under orders from Chiang to minimize casualties, failed to press their attacks, putting the Americans in an awkward situation. Taking advantage of the slow Chinese advance, Lt. Gen. Shinichi Tanaka, commander of the 18th Division, launched heavy attacks against the GALAHAD roadblocks. GALAHAD'S infantry, which had only mortars to counter Japanese field artillery, held on grimly, losing about 200 men but inflicting 800 casualties. As Chinese reinforcements began to arrive on 7 March Merrill withdrew his weary men from their positions. By then, the enemy had bypassed the roadblocks and had fallen back to a line along the rugged Jambu Bum range near Shaduzup (Map 10).

|

Anxious to capture the Jambu Bum before the onset of the monsoon season in June paralyzed offensive operations, Stilwell directed a resumption of the offensive on 12 March. Accompanied by the Chinese 113th Regiment, GALAHAD'S 1st Battalion outflanked the Japanese right, negotiating steep slopes and bypassing Japanese positions by slowly hacking its way through the dense undergrowth. In the course of the march the battalion crossed one stream fifty-six times. Early on the morning of 28 March the advance surprised an enemy camp south of Shaduzup and established a roadblock. Farther south, the other two battalions moved to cut the road at Inkangahtawng, but the 2d Battalion had no sooner established a blocking position than both battalions received orders from Stilwell's headquarters to head off a major Japanese drive against the flank of the Allied advance. Abandoning its prepared positions under fire, the 2d Battalion moved east to an isolated ridgeline at Nhpum Ga. Up to this point, Stilwell's headquarters had used GALAHAD as a flanking force that would only hold blocking positions for brief periods of time. As the official history points out, the change to a static defensive role at Nhpum Ga represented a radical change in the concept of GALAHAD's employment.

For eleven days the 2d Battalion, isolated and surrounded at Nhpum Ga, withstood heavy attacks and shelling, while the 1 st and 3d attempted to break through to them. Within the perimeter, lack of water and the pervasive stench of mule carcasses tortured the defenders; only a few supply drops made their position tenable. The defense was aided by the presence of Nisei (Japanese-American) interpreters, who overheard enemy orders and frequently confused the enemy by shouting directives in Japanese. Meanwhile, Merrill had been evacuated after suffering a heart attack, leaving Hunter in command of GALAHAD. Supported by artillery airdropped to them, the 1st and 3d Battalions finally reached the 2d on 9 April, and the Japanese withdrew south.

With the Jambu Bum in Allied hands, the 1,400 surviving Marauders anticipated a lengthy rest. But Stilwell had other ideas. He ordered the unit, accompanied by Chinese regiments and some Kachin irregulars, to seize the airfield at Myitkyina. The American commander recognized the poor condition of the Marauders but believed he had no alternative if the Allies were to capture Myitkyina before the monsoon. He promised to evacuate GALAHAD without delay "if everything worked out as expected."

Revived somewhat by Stilwell's pledge, GALAHAD began a 65-mile march over the 6,000-foot Kumon Range to Myitkyina. As 1st Lt. Charlton Ogburn later wrote, "We set off with that what-the-hell-did-you-expect-anyway spirit that served the 5307th [GALAHAD] in place of morale, and I dare say served it better. Mere morale would never have carried us through the country we now had to cross.... The saw-toothed ridges would have been difficult enough to traverse when dry. Greased with mud, the trail that went over them was all but impossible." 31 Mules fell off ledges to their deaths in the crevices below. Marauders left their packs by the side of the trail; straggling was rampant. Despite all the obstacles, the Marauders and their allies surprised the defenders of the air base on 17 May, seized the strip, and probed toward Myitkyina itself. Lacking a plan to follow up its initial success and reliable intelligence on the strength of the Japanese defense, the task force faltered in its attempts to take the city.

|

|

The Final Campaigns in Burma

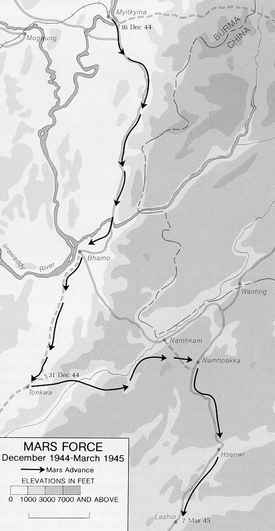

From August to December 1944 Detachment 101 aided the Allied advance to a phase line from Katha to Bhamo. In Area III Maddox's partisans filled a 200-mile gap between Chinese and American forces to the north and the British Fourteenth Army to the west.

|

The fall of Bhamo opened the way for an advance to the old Burma Road. As the detachment left the familiar Kachin highlands and entered the more open terrain inhabited by the Shans and Karens, its leaders expressed some concern that local support would evaporate. However, a combination of Allied victories and Japanese misrule enabled the detachment to work with the local tribes and even recruit several Shan and Karen guerrillas.

|

|

Although Peers had originally planned to deactivate Detachment 101 once the Burma Road had been reached, the critical situation in China and the diversion of Chinese and U.S. troops to that front caused theater headquarters to request that the Kachin battalions be retained. By this time many of the tribesmen were already hundreds of miles from their homes, some of which were threatened by Chinese bandits, but about 1,500 volunteered for a final offensive to secure the Burma Road by a general advance south. Joined by about 1,500 Karen, Gurkha, Shan, and Chinese volunteers, the Kachins, beginning in April 1945, infiltrated again into Japanese territory, established bases, and harassed Japanese communications, particularly the Taunggyi-Kentung Road along which Japanese troops were trying to escape to Thailand. By this time the remaining Japanese in the area were in poor condition, but their rear guards still fought hard in defense of fixed positions. In desperate fighting at Loilem, Lawksawk, and Pangtara, the Kachins, despite some air support, suffered their heaviest losses of the campaign. By mid-June, however, they had inflicted 1,200 casualties on the Japanese and had driven them from the Taunggyi-Kentung region, an achievement for which Detachment 101 later received the Distinguished Unit Citation. With the deactivation of the detachment on 12 July the native troops at last returned to their homes, and the Americans joined the growing OSS organization in China.