Egypt in World War II

Country study from Library of Congress

Mideast from CMH

|

In September 1918, Egypt made the first moves toward the formation of a wafd, or delegation, to voice its demands for independence at the Paris Peace Conference. On February 28, 1922, Britain unilaterally declared Egyptian independence without any negotiations with Egypt. Four matters were "absolutely reserved to the discretion" of the British government until agreements concerning them could be negotiated: the security of communications of the British Empire in Egypt; the defense of Egypt against all foreign aggressors or interference, direct or indirect; the protection of foreign interests in Egypt and the protection of minorities; and Sudan. Sultan Ahmad Fuad became King Fuad I, and his son, Faruk, was named as his heir. On April 19, a new constitution was approved. Also that month, an electoral law was issued that ushered in a new phase in Egypt's political development--parliamentary elections. On April 28, 1936, King Fuad died and was succeeded by his son, Faruk. In the May elections, the Wafd won 89 percent of the vote and 157 seats in Parliament.

Negotiations with the British for a treaty to resolve matters that had been left outstanding since 1922 had resumed. The British delegation was led by its high commissioner, Miles Lampson, and the Egyptian delegation by Wafdist leader and prime minister, Mustafa Nahhas. On August 26, a draft treaty that came to be known as the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 was signed. The treaty provided for an Anglo-Egyptian military and defense alliance that allowed Britain to maintain a garrison of 10,000 men in the Suez Canal Zone. In addition, Britain was left in virtual control of Sudan. This contradicted the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium Agreement of 1899 that provided that Sudan be governed by Egypt and Britain jointly. In spite of the agreement, however, real power was in British hands. Egyptian army units had been withdrawn from Sudan in the aftermath of the Stack assassination, and the governor general was British. Nevertheless, Egyptian nationalists, and the Wafd particularly, continued to demand full Egyptian control of Sudan. The treaty did provide for the end of the capitulations and the phasing out of the mixed courts. The British high commissioner was redesignated ambassador to Egypt, and when the British inspector general of the Egyptian army retired, an Egyptian officer was appointed to replace him. In spite of these advances, the treaty did not give Egypt full independence, and its signing produced a wave of antiWafdist and anti-British demonstrations.

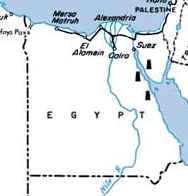

With the beginning of World War II, Egypt again became vital to Britain's defense. Britain had to assure, if not the wholehearted support of Egypt, at least its acquiescence in British military and political policies during the crisis. For its part, Egypt considered the war a European conflict and hoped to avoid being entangled in it. As one Axis victory succeeded another, Egyptians grew increasingly convinced that Germany would win the war. Some were pleased at the prospect of a German victory, not because they were attracted to the Nazi ideology, but because they viewed any enemy of their enemy, Britain, as a friend. Meanwhile, the British were determined to prevent an Egyptian-German alliance. The war gave the Wafd the opportunity to return to power. The Wafd set out to convince the British that they would not lead an anti-British insurrection during the wartime crisis. Uncertain of the loyalty of Prime Minister Ali Maher and convinced that the king was intriguing against them, the British decided to entrust the Egyptian government to the Wafd. On February 2, 1942, with the German army under General Erwin Rommel advancing toward Egypt, Lampson, the British ambassador, ordered the king to ask Mustafa Nahhas, the Wafdist leader, to form a government. The incident clearly demonstrated that real power in Egypt resided in British hands and that the king and the political parties existed only so long as Britain was prepared to tolerate them. It also eroded popular support for the Wafd because it showed that the Wafd would make an alliance with the British for purely political reasons. The Wafd's credibility was eroded further in 1943 when a disaffected former Wafd member, Makram Ubayd, published his Black Book. The book contained details of Nahhas's corrupt dealings over the years and seriously damaged his reputation.

The Wafdist government fell in 1944, and the Wafd boycotted the elections of 1945, which brought a government of Liberal Constitutionalists and Saadists to power. As World War II ended, the Wafd was splintered into several competing camps. The political initiative and popular support swung toward the militant organizations on the right, such as the Muslim Brotherhood and Young Egypt.

In 1945 a Labour Party government with anti-imperialist leanings was elected in Britain. This election encouraged Egyptians to believe that Britain would change its policy. The end of the war in Europe and the Pacific, however, saw the beginning of a new kind of global war, the Cold War, in which Egypt found itself embroiled against its will. Concerned by the possibility of expansion by the Soviet Union, the West would come to see the Middle East as a vital element in its postwar strategy of "containment." In addition, pro-imperialist British Conservatives like Winston Churchill spoke of Britain's "rightful position" in the Suez Canal Zone. He and Anthony Eden, the Conservative Party spokesman on foreign affairs, stressed the vital importance of the Suez Canal as an imperial lifeline and claimed international security would be threatened by British withdrawal.

In December 1945, Egyptian prime minister Mahmud Nuqrashi, sent a note to the British demanding that they renegotiate the 1936 treaty and evacuate British troops from the country. Britain refused. Riots and demonstrations by students and workers broke out in Cairo and Alexandria, accompanied by attacks on British property and personnel. The new Egyptian prime minister, Ismail Sidqi, a driving force behind Egyptian politics in the 1930s and now seventy-one and in poor health, took over negotiations with the British. The British Labour Party prime minister, Clement Atlee, agreed to remove British troops from Egyptian cities and bases by September 1949. The British had withdrawn their troops to the Suez Canal Zone when negotiations foundered over the issue of Sudan. Britain said Sudan was ready for self-government while Egyptian nationalists were proclaiming "the unity of the Nile Valley," that is, that Sudan should be part of Egypt. Sidqi resigned in December 1946 and was succeeded by Nuqrashi, who referred the question of Sudan to the newly created United Nations (UN) during the following year. The Brotherhood called for strikes and a jihad (holy war) against the British, and newspapers called for a guerrilla war.

In 1948 another event strengthened the Egyptian desire to rid the country of imperial domination. This event was the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel by David Ben-Gurion in Tel Aviv. The Egyptians, like most Arabs, considered the State of Israel a creation of Western, specifically British, imperialism and an alien entity in the Arab homeland. In September 1947, the League of Arab States (Arab League) had decided to resist by force the UN plan for partition of Palestine into an Arab and a Jewish state. Thus, when Israel announced its independence in 1948, the armies of the various Arab states, including Egypt, entered Palestine to save the country for the Arabs against what they considered Zionist aggression. The Arabs were defeated by Israel, although the Arab Legion of Transjordan held onto the Old City of Jerusalem and the West Bank (see Glossary), and Egypt saved a strip of territory around Gaza that became known as the Gaza Strip.

When the war began, the Egyptian army was poorly prepared and had no plan for coordination with the other Arab states. Although there were individual heroic acts of resistance, the army did not perform well, and nothing could disguise the defeat or mitigate the intense feeling of shame. After the war, there were scandals over the inferior equipment issued to the military, and the king and government were blamed for treacherously abandoning the army. One of the men who served in the war was Gamal Abdul Nasser, who commanded an army unit in Palestine and was wounded in the chest. Nasser was dismayed by the inefficiency and lack of preparation of the army. In the battle for the Negev Desert in October 1948, Nasser and his unit were trapped at Falluja, near Beersheba. The unit held out and was eventually able to counterattack. This event assumed great importance for Nasser, who saw it as a symbol of his country's determination to free Egypt from all forms of oppression, internal and external. Nasser organized a clandestine group inside the army called the Free Officers. After the war against Israel, the Free Officers began to plan for a revolutionary overthrow of the government. In 1949 nine of the Free Officers formed the Committee of the Free Officers' Movement; in 1950 Nasser was elected chairman."

Links:

Europe 1943 | Timeline start | Links | Pictures | Maps | Documents | Bibliography | revised 11/14/02