|

"The American campaign against the Japanese on Okinawa still raged when a war correspondent new to the Pacific theater stepped ashore on Ie Shima, a small island just west of Okinawa. Traveling with a group of infantrymen, the reporter was killed by a sniper's machine-gun bullets. Saddened by their loss, the soldiers paid tribute to their fallen friend with a simple plaque reading: "At this spot, the 77th Infantry Division lost a Buddy, Ernie Pyle, 18 April 1945." To the millions on the American home front during World War II, Ernie Pyle's column offered a foxhole view of the struggle as he reported on the life, and sometimes death, of the average soldier. When he died, Pyle's readership was worldwide, with his column appearing in 400 daily and 300 weekly newspapers. Noble Prize-winning author John Steinbeck, a Pyle friend, perhaps summed up the reporter's work best when he told a Time magazine reporter: "There are really two wars and they haven't much to do with each other. There is the war of maps and logistics, of campaigns, of ballistics, armies, divisions and regiments--and that is General [George] Marshall's war. Then there is the war of the homesick, weary, funny, violent, common men who wash their socks in their helmets, complain about the food, whistle at the Arab girls, or any girls for that matter, and bring themselves through as dirty a business as the world has ever seen and do it with humor and dignity and courage--and that is Ernie Pyle's war." Ernest Taylor Pyle was born on Aug. 3, 1900, on the Sam Elder farm, located south and west of Dana, where his father was then tenant farming. Pyle, the only child of Will and Maria Pyle, disliked farming, once noting that "anything was better than looking at the south end of a horse going north." After his high school graduation, Pyle--caught up in the patriotic fever sweeping the nation upon America's entry into World War I--enlisted in the Naval Reserve. Before he could complete his training, however, an armistice was declared in Europe. In 1919 Pyle enrolled at Indiana University in Bloomington. He left the university in 1923, just short of finishing a degree in journalism, to accept a reporter's job at the LaPorte Herald. A few months later, lured by an offer of an extra $2.50 per week, Pyle joined the staff of the Washington (D.C.) Daily News, part of the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain. On July 25, 1925, Pyle married Minnesota native Geraldine Siebolds. By 1926 the Pyles had quit their jobs to barnstorm around the country, traveling 9,000 miles in just 10 weeks. Pyle returned to the Washington Daily News in 1927 and began the country's first-ever daily aviation column. He was the newspaper's managing editor for three years before becoming a roving columnist for Scripps-Howard. In the next six years, he crossed the continent some 35 times. Columns from this period were compiled in the book Home Country. Pyle journeyed to England in 1940 to report on the Battle of Britain. Witnessing a German fire-bombing raid on London, he wrote that it was "the most hateful, most beautiful single scene I have ever known." A book of his experiences during this time, Ernie Pyle in England, was published in 1941. A year later he began covering America's involvement in the war, reporting on Allied operations in North Africa, Sicily, Italy and France. The columns he wrote based on his experiences during these campaigns are contained in the books Here is Your War and Brave Men. Although Pyle's columns covered almost every branch of the service--from quartermaster troops to pilots--he saved his highest praise and devotion for the common foot soldier. "I love the infantry because they are the underdogs," he wrote. "They are the mud-rain-frost-and-wind boys. They have no comforts, and they even learn to live without the necessities. And in the end they are the guys that wars can't be won without." The Hoosier reporter's columns not only described the soldier's hardships, but also spoke out on his behalf. In a column from Italy in 1944, Pyle proposed that combat soldiers be given "fight pay," similar to an airman's flight pay. In May of that year, Congress acted on Pyle's suggestion, giving soldiers 50 percent extra pay for combat service, legislation nicknamed "the Ernie Pyle bill." Despite the warmth he felt for the average G.I., Pyle had no illusions about the dangers involved with his job. He once wrote a friend that he tried "not to take any foolish chances, but there's just no way to play it completely safe and still do your job." Weary from his work in Europe, Pyle grudgingly accepted what was to be his last assignment, covering the action in the Pacific with the Navy and Marines. He rationalized his acceptance, noting, "What can a guy do? I know millions of others who are reluctant too, and they can't even get home." The infantrymen who received Pyle's body after his death found in his pockets a draft of a column he intended to release when the war in Europe ended. In that column Pyle wrote that he would not soon forget "the unnatural sight of cold dead men scattered over the hillsides and in the ditches along the high rows of hedge throughout the world. "Dead men by mass production--in one country after another--month after month and year after year. Dead men in winter and dead men in summer. "Dead men in such familiar promiscuity that they become monotonous. "Dead men in such monstrous infinity that you come almost to hate them." (Biographical sketch from the Indiana Historical Society) |

|

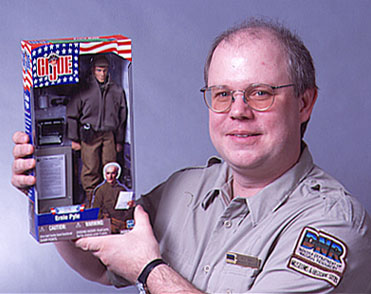

Ernie Pyle

photo from USS Cabot |

|

Ernie Pyle home in Dana IN,

from Indiana State Museum 2002 |

|

Ernie Pyle home in Albuquerque NM, photo by Bianca Clinch 8/02

|

|

exhibit in Ernie Pyle home in Albuquerque NM, photo by Bianca Clinch 8/02 - big

|

|

exhibit in Ernie Pyle home in Albuquerque NM, photo by Bianca Clinch 8/02

|