|

|

"Old Skull Given White Looks, Inciting Dispute," by Timothy Egan, New York Times, April 2, 1998

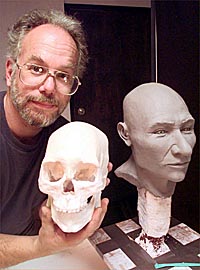

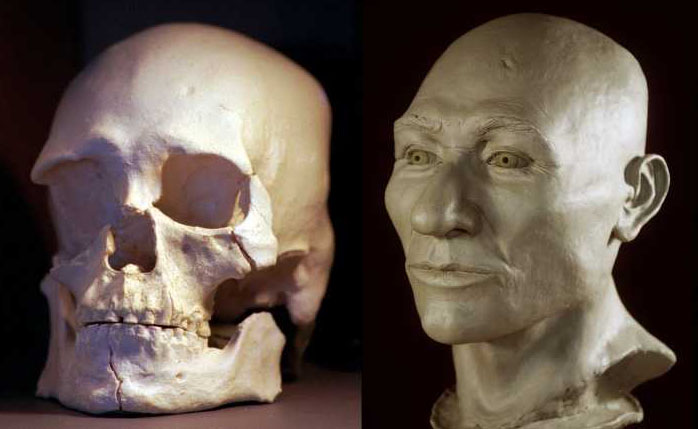

SEATTLE -- One of the oldest and most nearly complete sets of human remains ever found in North America was given a face last month in a reconstruction by James Chatters, the anthropologist who first analyzed the find. In clay flesh, the 9,300-year-old face of what is known as Kennewick Man looks like Patrick Stewart, the "Star Trek" actor. If the anthropological casting seems inspired to some, it has heightened an already bitter and muddled battle over the rights to Kennewick Man's remains and his origins. It is a battle that extends to questions of race and the origins of the first Americans. While the fate of Kennewick Man is determined in court, his remains are locked away, inaccessible to the scientists who want to study him and the Indians who want to bury him. But by giving a late-Pleistocene-era skull the face of a late-20th-century British actor, some anthropologists say, Chatters has given a racial identification to something that has already been said to defy racial categories. As Alan H. Goodman, a professor of anthropology at Hampshire College in Amherst, Mass., put it, "Kennewick Man has become a textbook example of why race science is bad science."

When the bones were discovered in the summer of 1996 along the banks of the Columbia River, in southeastern Washington State, they electrified researchers. Virtually intact, with features described by some anthropologists as both European and Asian, Kennewick Man held the possibility of providing new answers to the many questions about how the Americas were peopled. But the skull and bones have been under lock and key for 19 months now, as a three-way legal battle is being fought over the remains. Researchers have sued to gain access to the bones for research. The Umatilla Indians of the Columbia plateau say Kennewick Man is their ancestor. They have filed suit to get the remains so they can give them a proper burial. They say they have that right under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which requires that human remains and artifacts be returned to Indian tribes that can show a cultural link. A California pagan group, the Asatru Folk Assembly, says Kennewick man was a white ancestor to modern-day Europeans. The group has also sued so they can give the remains a burial using ceremonies of pre-Christian Norse worship. They have also been allowed to perform religious rituals at the site. "Especially after seeing Dr. Chatters' reconstruction, there is no doubt in my mind that Kennewick Man is an ancestor of the people who became Europeans," Michael Clinton, the lawyer for the group, said in an interview. "Kennewick Man is a threat to the Indians because he jeopardizes their moral authority and argument that they were the victims of Europeans which succeeded them."

White supremacists are among those who have used Kennewick Man to claim that Caucasians came to America well before Indians and a group that monitors racist organizations has linked some present and former members of Asatru with white power groups. "Asatru Folk Assembly is a racialist religion, a hate group," said Jonathan Mozzochi, the research director for the Coalition for Human Dignity, a organization in Seattle that monitors far-right groups. Clinton, the group's lawyer, said that some neo-Nazi sympathizers used to belong to Asatru but that they have since been expelled. He calls the coalition report "a smear" intended to weaken the Asatru claim to the bones. Responding to reports of supremacist opposition to the Indian claims, some anthropologists have stepped up their criticism of the racial classification of Kennewick Man. "The academic debate is one thing, but it's a whole other game to think about how this is being used politically," said Goodman, the Hampshire College anthropologist, who has written articles in professional journals urging fellow researchers to reject making racial distinctions in archaeological finds.

As the debate and court case go on, researchers fear that their chances for further study are slipping away. All research was halted by the government 19 months ago, pending a resolution to the various claims. Many researchers with intense interest in the remains are angry over how the United States Army Corps of Engineers, which has jurisdiction over the site on the Columbia River where the bones were discovered, has cared for the bones and the site. The bones are sealed in plastic and stored in a box near Kennewick, under the agency's care. A recent report indicated that some of Kennewick Man's bones may be missing and the Justice Department is investigating a discrepancy between the list of remains that Chatters turned over to the Corps and a recent inventory by federal officials. "These are big pieces, from two femurs, and they didn't just walk away by themselves," said Alan Schneider, a Portland, Ore., lawyer who represents eight prominent researchers suing the government for the right to study Kennewick Man.

The race question arose, Chatters said in an interview, because he was forced by the native graves law to make a racial distinction. When the bones were discovered by two boys, Chatters, who is a consultant to the Benton County Coroner, was asked to examine them. The skull has a long face, square jaw, somewhat narrow cranial cavity, with the teeth largely intact. Chatters initially thought it was an early white settler. But radio-carbon dating placed the bones at an age of about 9,300 years. Only about seven intact skeletons of that age have been found in the Americas. Chatters and two associates determined the skeleton to be "Caucasoid," saying it did not match any known Indian features. Caucasoid can refer to some southern Asian groups as well as Europeans. "Nobody is talking white here," said Chatters in his address last week to the 63rd annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology. "We're just talking about physical characteristics."

But the question arises as to why Chatters, in his recent casting of the image, made Kennewick Man look white, like Patrick Stewart. He said it was because as he had tried to visualize the skull, the "Star Trek" star is what most strongly came to mind. Using a plaster cast of the skull and measurements he had made, Chatters said he and a sculptor had given further shape to the skull by simply following the bone and cranial structure. Skin color is no consideration, he said, adding that all Kennewick Man proves so far is how much rethinking is needed on how people came to the Americas. "We thought we had it all figured out, didn't we?" Chatters said in addressing archaeologists at their annual meeting, which ended in Seattle on Sunday. Critics like Goodman of Hampshire College said it was entirely possible that Kennewick Man could be dark-skinned. "I really do object to saying there is such a thing as a Caucasoid trait," Goodman said in an interview. "You can find amazing changes in cranial size just within certain groups that lived in the same area."

But other researchers agree with Chatters that the issue of race was forced on him because the Indian burial laws required an ethnic determination. "This law puts you in a position of having to make a call before you can do any real extensive studies," said Dr. Robson Bonnichsen, director of the Center for the Study of the First Americans at Oregon State University, in Corvallis. Bonnichsen is one of eight scientists suing to study Kennewick Man. The Umatillas, who live in the central Columbia River region, say Kennewick Man is their ancestor. If the court rules for them, they say, they will bury the remains, as the law allows them to do. But even researchers like Goodman, who are sympathetic to the tribe's position, say such a burial would be a huge loss to science. Science got a bit of a reprieve on Tuesday when the Army Corps of Engineers agreed that unless it got permission from the federal judge hearing the court cases, it would not go forward with its plan to protect the Columbia River site by covering it with boulders, sand and stone. Many researchers said the corps project amounted to government vandalism.

PORTLAND, Ore. (AP ) ‹ In a setback to scientists, the U.S. Interior Department decided Monday that Kennewick Man, one of the oldest skeletons ever found in North America, should be given to five American Indian tribes who have claimed him as an ancestor. The decision comes after four years of dispute between the tribes ‹ who want the remains buried immediately ‹ and researchers, who want to continue studying the 9,000-year-old bones that have already forced anthropologists to rethink theories about where the original Americans came from.

Some facts about Kennewick Man, the ancient skeleton found in 1996: The remains: In all, 380 bones and bone fragments from an ancient human skeleton. Approximately 80% of the skeleton was recovered. Where: In Columbia River, near Kennewick, Wash., by college students. Approximate age: Carbon dating from a bone sliver indicated the skeleton is 9,320 to 9,510 years old. Height: 5 feet, 9 inches. Age at death: mid-40s. General description: The man's face was narrow, with a large, protruding nose. He had a slight depression above the left eye, likely from a minor injury. He was very muscular. Experts disagree about his injuries, which included three to six broken ribs, a broken left elbow and a projectile point embedded in the pelvis.

The controversy: Five American Indian tribes claim Kennewick Man is an ancestor and want the remains buried immediately. Researchers have sued for the right to continue their study of the skeleton.Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt said the remains were ''culturally affiliated'' with the five tribes and were found in the Columbia River shallows near the tribes' aboriginal lands. ''Although ambiguities in the data made this a close call, I was persuaded by the geographic data and oral histories of the five tribes that collectively assert they are the descendants of people who have been in the region of the Upper Columbia Plateau for a very long time,'' Babbitt said in a statement.

However, the fate of the bones may be decided in court. Eight anthropologists, including one from the Smithsonian Institution, have filed a lawsuit in federal court in Portland for the right to study the bones. The remains are being kept at the Burke Museum of Natural and Cultural History in Seattle. The lawsuit was put on hold pending the Interior Department research. Now that Babbitt has issued his determination, the scientists say they will ask the judge to let the lawsuit go forward. ''Every decision they have made in the four years since the litigation was filed has been consistent with having a closed mind from the start,'' said Paula Barron, a lawyer for the scientists.

Found in 1996, Kennewick Man is one of the most complete skeletons found in North America. Radiocarbon-dating of the 380 bones and skeletal fragments place their age at between 9,320 and 9,510 years old. The disposition of the bones has been hotly contested ever since the first anthropologist to examine Kennewick Man claimed the skull bore little resemblance to today's Indian people. The Interior Department agreed to determine what should happen to the bones under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990. The bones were found on federal land managed by county government in Kennewick, Wash.

Professors who studied the bones for the Interior Department have said Kennewick Man appears to be most strongly connected to the people of Polynesia and southern Asia. The find helped force researchers to consider the possibility that the continent's earliest arrivals came not by a land bridge between Russia and Alaska ‹ a long-held theory ‹ but by boat or some other route. Pieces of the skeleton were sent to three laboratories, but none was able to extract DNA for analysis. ''Clearly, when dealing with human remains of this antiquity, concrete evidence is often scanty, and the analysis of the data can yield ambiguous, inconclusive or even contradictory results,'' Babbitt said. He said if the remains had been 3,000 years old, ''there would be little debate over whether Kennewick Man was the ancestor of the Upper Plateau Tribes.'' But ''the line back to 9,000 years ... made the cultural affiliation determination difficult,'' he said.