|

|

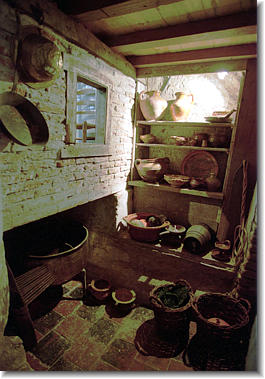

The museum, funded with help from the Mayflower Society, the Pilgrim Society and the New England Historic Genealogical Society, is in a typical Pilgrim-style 16th century one-room house. The place is packed with Pilgrim-era tools, pottery and furniture, including a cabinet containing tobacco pipes, coins, buttons and toys. ``We'll take these items out and have conversations,'' said Bangs, 51, who has authored 10 books about the Pilgrims. ``People will learn in this intimate way.'' The Pilgrims brought with them to Plymouth Colony many Dutch ways, such as the civil registration of marriages. John Quincy Adams would later hail their Mayflower Compact as the foundation for the U.S. Constitution.

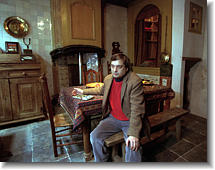

Bangs originally came to Leiden, the birthplace of Rembrandt 25 miles southwest of Amsterdam, to study Dutch art and architecture. He ended up running the city's Pilgrim archives, and when it closed a few years ago, he decided to stay. His own home betrays his passion. Original engravings of Pilgrim life clutter a coffee table; a Pilgrim-era ladderback chair occupies a corner of his kitchen. ``We really don't know much about what Pilgrim family life was like,'' he said. ``That's the goal of this house museum -- to give some sense of how they lived.''

"Government in the Netherlands Thwarts Modern Pilgrim's Progress," by Fox Butterfield, New York Times, December 31, 1998

BOSTON -- Almost four centuries after the Netherlands gave the Pilgrims refuge from persecution in England, a leading American scholar on the Pilgrims seems to have been caught in the Dutch Government's crackdown on immigrants and has been ordered to leave the Netherlands by Jan. 15. The scholar, Dr. Jeremy Bangs, who founded a Pilgrim museum last year in Leiden, said the Dutch Ministry of Justice had rejected his application for permanent residency because, it said, he did not qualify for a work permit and it did not believe he could support himself. "It is hard to get more ironic than to expel someone who is working on the Pilgrims, who were the most famous example of Dutch welcome and protection," Dr. Bangs said. At the time the Pilgrims fled to the Netherlands in 1608, he said, the government boasted that it "refuses no honest people free entry."

Dr. Bangs, 52, receives financial support from the New England Historic Genealogical Society in Boston to conduct research on the history of the Pilgrims while they were in the Netherlands before leaving for America in 1620 and founding Plymouth. He recently discovered the first contemporary painting showing the Pilgrims embarking at Delftshaven on their way to America. Jane Fiske, the editor of the Register of the Historic Genealogical Society, which will publish an article about Dr. Bangs's discovery in January, said of the deportation, ""He has done so well in his research and opening the museum that this whole thing seems ludicrous."

The Ministry of Justice has been trying to deal with a record 50,000 illegal immigrants to the Netherlands, already one of the most densely populated countries, from Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia and the former Yugoslavia this year. The immigrants contend that they are escaping political persecution, but the Dutch Government has been under pressure to treat them as economic refugees and expel them. A spokesman for the ministry, Wijnand Stevens, said Dr. Bangs could appeal the expulsion. Stevens also said the Government's crackdown and Dr. Bangs's case were not related. But the leading Dutch newspaper, NRC Handelsblad, poked fun at the ministry on Tuesday, suggesting that Dr. Bangs was a victim of bureaucratic stupidity. The problem for Dr. Bangs is that he may not apply for a work permit because he is both an employee of the Leiden American Pilgrim Museum and the director of it, the paper said. Under Dutch law, only an employer may apply for a permit for an employee, so, the paper said, Dr. Bangs "falls outside bureaucratic definition." "Bangs does not cost the Dutch state a single penny," the paper said. "And his museum tells of a meaningful part of our history. Hillary Rodham Clinton who will visit the Netherlands in February has put the museum on her agenda. Perhaps she will arrive at a closed door because Bangs had to leave the Netherlands on Jan. 15. Can someone explain this to Hillary?" At least one member of the Dutch Parliament, J. Th. Hoekema, has officially questioned the ministry's decision. Friends and acquaintances of Dr. Bangs say another part of his difficulty may be that he lives simply, on the small income from the Historic Genealogical Society and that the ministry may not believe he has enough means of support. Neither Dr. Bangs nor the society would say what he is paid, but Ms. Fiske said: "He lives very frugally, in a small apartment in an old building, and it is hard to see how he gets by. I think he is putting much of the money we give him into the museum."

Before moving to Leiden two years ago, Dr. Bangs lived in Scituate, Mass., and was curator of Plimouth Plantation. He holds a doctorate in history from the University of Leiden and has written 12 books and more than 40 scholarly articles. In his research, he has demonstrated that some of the people Americans today celebrate as the Pilgrims were not English. Several were French-speaking Walloons, or Protestants, and one even came from Danzig, in Poland. They had all come to Leiden because it was a center of religious tolerance at a time of warfare between Catholics and Protestants. Dr. Bangs said that if he was required to leave, the museum would probably close. If he does have to abandon Leiden, he may recall a passage written about the Pilgrims' departure in 1620 by William Bradford, later Governor of Plymouth: "So they left that goodly and pleasant city which had been their resting place near twelve years; but they knew they were pilgrims, and looked not much on those things, but lift up their eyes to the heavens, their dearest country, and quieted their spirits."

|

|