|

|

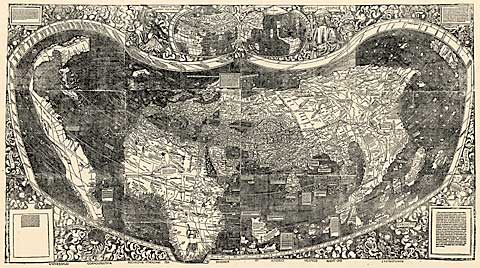

The world map, a woodcut print on paper in 12 sections, 8 by 4 1/2 feet altogether, is also of considerable interest to scholars because it is thought to be the first cartographic depiction of the Americas as a land mass separate from Asia. Even after 15 years of European explorations, mapmakers had until then continued to draw a tripartite world composed of only Europe, Africa and Asia, with the new lands represented as vague appendages of Asia. The coastline from Newfoundland to Argentina is limned with a seeming authority that probably exceeded the known facts. The northern continent is a narrow wisp of land, but the southern continent bears a hint of its true shape. In another of the map's innovations, a wide ocean stretches between the new lands and Asia, the first representation of the Pacific as a separate body of water.

Most learned people at the time had not conceived of a world large enough for such a sizable ocean, and apparently no geographical discoveries had by then occurred to change minds. Balboa would not cast eyes on the Pacific, in Panama, until 1513, and it would be 1519 before Magellan set off on the voyage that first took Europeans across the Pacific. "With this map, the world is beginning to look like something we can recognize," said Dr. John R. Hebert, chief of the library's geography and map division. Like other scholars, Dr. Hebert said he doubted that those who drew this map possessed any secret knowledge leading them to separate the new continents from Asia and place a great ocean in between. "They probably made a scholarly surmise, really a leap of faith," he said. If that was the case, this was hardly the last time mapmakers appeared to get ahead of knowledge, but it proved to be prescient. In the 1950's, Dr. Hebert recalled, cartographers took a similar leap of faith in compiling from sketchy soundings the first maps of a vast mountain range under the sea, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Dr. Hebert said the Waldseemüller map was in excellent condition and was expected to be put on public display in Washington this fall. Conservators are pressing and treating the individual map sheets to restore them to their original flatness. The library will then prepare a facsimile, which will be used most of the time in displays. In an agreement approved by the German government, the library acquired the map from Prince Johannes Waldburg-Wolfegg, whose family castle in Baden-Württemberg had been the map's home for more than 350 years. The map originally belonged to Johann Schöner, a 16th- century astronomer-geographer. Long thought to be lost, the only known copy of the map was rediscovered in the castle in 1901.

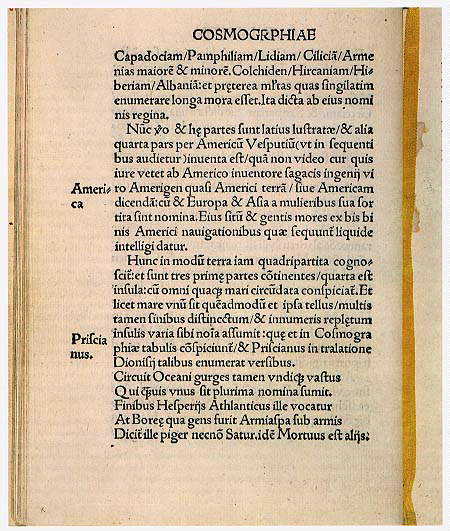

The map was the product of a community of scholars and clerics in the village of St.-Dié in Lorraine. Their patron, René II, the Duke of Lorraine, had received a copy of Vespucci's recently published account of his explorations along the South American coasts, as well as a map depicting the newfound regions. When the materials came into their hands, the scholars immediately went to work on a new world map and a 103-page book, "Cosmographiae Introductio," describing the new geographical knowledge. The man given the most credit for the book and the map was Martin Waldseemüller, an illustrator and cartographer from southern Germany. Noting that Vespucci had recently discovered "a fourth part" of the world, Waldseemüller delivered the book's most sensational proposal. "Since Europa and Asia have received names of women," he wrote, "I see no reason why we should not call this other part `Amerige,' that is to say, the land of Americus, or America, after the sagacious discoverer Americus." The cartographer might have been influenced in conceiving the name by a young colleague, Matthias Ringmann, who was fond of words and geographical names and was a bit of a romantic.

The name America was affixed only to the southern continent, with the north left unnamed. On the full map, the two continents are separated by a strait, but on an inset map, they are joined at the Isthmus of Panama. Historians have often pondered the possible reasons for choosing Vespucci over Columbus. Perhaps it was because Columbus had gone to his grave the year before still convinced that he had at least reached the fringes of his goal of the Indies ‹ Asia. Vespucci, on the other hand, had recently written a letter, significantly titled "Mondus Novus," in which he claimed to have found "what we may rightly call a New World." In any case, successors like Vespucci were eclipsing Columbus's fame. Vespucci wrote vivid descriptions of the scenery and customs of the new lands, and that attracted a wide audience, including the scholars in Lorraine. But at least one researcher has suggested that the naming of America was a deliberate snub of Columbus. "It was not a stupid mistake," said Peter Dickson, an independent scholar in Washington and former analyst at the Central Intelligence Agency. "They thought it through."

Mr. Dickson said that in his research for a book on Columbus, yet to be published, he found evidence indicating that the 1507 map had reflected Portuguese interests and that Columbus had been held in low regard in Lisbon, in part because he had sailed for Spain and might have been involved in intrigues against the Portuguese crown. Columbus, Mr. Dickson said, was "a person with a lot of political baggage from Lisbon's perspective." Dr. Hebert said that some of Mr. Dickson's research about Columbus's life in Portugal was "very interesting." But on the naming question, most scholars would probably agree with the explanation offered by Dr. Woodward of Wisconsin. "Somehow Vespucci had a better public relations department," he said. Columbus might have been slighted, but not completely ignored. On a section of the map showing the Caribbean, Waldseemüller wrote, "These islands were discovered by Columbus, an admiral of Genoa, at the command of the King of Spain."

The book and the map were immediate successes. The press at St.-Dié turned out more than 1,000 copies, making it a best seller by the standards of the day. Other cartographers applied the name America to a globe in 1509 and on several subsequent maps. Years later, having second thoughts, Waldseemüller and his colleagues removed the name from some editions. Why they did so, said Dr. Hebert, of the library, is "an even more intriguing part of the story." After the mapmaker's death in 1518, printers restored the name. Then, in 1538, the great cartographer Gerardus Mercator published a map of the world that extended the name to both continents, to North America and South America.

Dr. Daniel J. Boorstin, a historian and former librarian of Congress, has offered two ways of looking at the naming of America, each rich in irony. In a lecture in 1987, he remarked that the Waldseemüller map and book were an early demonstration of the "irreversible powers of the press." In his book "The Discoverers" (1983), Dr. Boorstin accepted the naming outcome with equanimity. "It was appropriate," he wrote, "that the name America should be affixed on the New World in a manner casual and accidental, since the European encounter with this new world had been so unintentional."

|

|