|

In 1869 he was elected as a Democrat to the United States Senate. His only previous experience in public office had been less than a year's service as United States attorney for Delaware in 1853-54. His friends considered his election as a tribute to his professional standing and high reputation for integrity and ability; his opponents, as evidence that the state was a pocket borough of the Bayard family. His service in the Senate, 1869-85, covered a period when the fortunes of his party were, in general, at a low ebb. Throughout most of his congressional career it was in the minority, and had relatively few men of outstanding ability in either house. Bayard acquired a recognized position almost from the start, but being a minority leader, he is naturally remembered rather for his opposition to Republican policies, for his exposure of abuses, for the energy with which he defended unpopular minorities and hopeless causes, than for constructive legislation or the successful solution of great problems. He was to the last a Democrat of the older school, although he lived to see a new generation abandon many of its historic principles for miscellaneous political and economic vagaries. He began by fighting the Reconstruction policies of the Radicals both because he considered them harsh and impolitic, and because they involved an undue centralization of federal power with a corresponding aggrandizement of the Executive branch of that Government. The currency, he declared, could not be "lawfully or safely anything else than a currency of value--The gold and silver coin directed by the Constitution" (Congressional Record, 43 Cong., 2 Sess., App., 971 ff.). He hated class legislation of every sort, whether it took the form of ship subsidies, railroad land grants, or tariff protection. Militarism and socialism he considered equally inimical to freedom. Lawmaking, he declared again and again, should be restricted to measures universally accepted as necessary, and administration should above all else be honest and frugal. Admirable as many of these doctrines appear in the abstract, it is hard to believe that he ever grasped the full significance of the changes wrought by the Civil War and the nationalization of economic and social life which followed it.

He was a candidate for the presidential nomination in 1880, and again in 1884, receiving considerable support. The exigencies of party politics, however, made his nomination impossible. He became secretary of state, Mar. 6, 1885, relinquishing his place in the Senate, it was believed, with some reluctance, and largely out of a desire to render President Cleveland any assistance in his power. As secretary, he was confronted with troublesome problems from the beginning of his term. A believer in civil service reforms, and on the whole successful in putting his beliefs into practise (Nation, Mar. 7, 1889), he found himself confronted with the demands of party workers whose hunger for patronage had been unsatisfied for twenty-five years. In spite of the fact that foreign governments "had schooled themselves against surprise" at the character of our diplomatic service, wrote one of his critics, some of Bayard's appointments "succeeded in startling more than one of them out of the composure which befits great kings and commonwealths" (Arthur Richmond, in North American Review, CXLVIII, 23). Thus Italy and Austria emphatically rejected A. M. Keily as persona non grata when appointed successively as minister to those countries, the correspondence thereon achieving the immortality which belongs to "classic cases" in textbooks of diplomacy and international law (documentary history of these incidents is found in Foreign Relations of the United States, 1885, pp. 28-57, and pp. 549-52). Toward the close of his administration Bayard had the equally unpleasant and famous task of dismissing the British minister for his unfortunate indiscretions during the presidential campaign of 1888 (Ibid., 1888, II, 16671729). The three major diplomatic issues of his term he was obliged to pass on unsettled to his successors. The North Atlantic fisheries question, that perennial source of friction, had suddenly become acute with the expiration of the "fisheries clauses" of the Washington Treaty, July 1, 1885. Complicated by the Canadian desire for tariff concessions, the subject caused a serious clash. Seizure of United States vessels in 1886-87 led to jingoistic talk of reprisals, and even war. The Secretary was apparently better acquainted than many of his critics with certain legal defects in the claims of the United States, and pursued a conciliatory policy which resulted in the Bayard-Chamberlain Treaty of Feb. 15, 1888. Assailed in many quarters as a surrender of United States rights, and considered in the Senate while the presidential campaign was in progress, it was rejected six months later. Fortunately a modus vivendi had been arranged to meet such a contingency. The other two issues arose in the Pacific. British protests at the seizure of Canadian sealing vessels in Bering Sea led Bayard to confer with interested powers regarding the protection of the seal herds by international agreement, but any such agreement was frustrated by Canadian objections, May 16, 1888, apparently in anticipation of the expected defeat of the Fisheries Treaty. Through June and July 1887, another conference with representatives of Germany and Great Britain wrestled unsuccessfully with the problem of adjusting conflicting interests in Samoa. It is also worth noting in view of subsequent developments that Bayard tendered the good offices of the United States (1886) to bring about a settlement of the boundaries dispute between Great Britain and Venezuela. If unsuccessful, his policies were at least consistently on the side of peace and arbitration and the subsequent outcome of the North Atlantic and Bering Sea disputes disproved some of the contentions put forward by opponents who charged him with failure to uphold United States "rights."

Following Cleveland's second inauguration, 1893, he was appointed ambassador to Great Britain, the first time such diplomatic rank had been conferred by the United States. He was in many respects a successful representative, but was probably better appreciated in London than at home. When the Venezuelan flurry of 1895-96 took place, he refused to be stampeded into unfriendly speech or action, and a letter to the President shows that he was perturbed at the prospect of allowing "the interests and welfare of our country to be imperiled or complicated by such a government and people as those of Venezuela" (R. M. McElroy, Grover Cleveland, II, 191). He worked quietly but steadily in the interests of Anglo-American friendship. "He did much to cement cordial relations," says Sir Willoughby Maycock, who had first met him when discussing the Fisheries Treaty some years before. "He entertained on a liberal scale, and was in addition a good sportsman, a keen deerstalker in the Highlands, while his face was not unfamiliar at Epsom, Ascot and Newmarket Heath" (With Mr. Chamberlain in the United States and Canada, 1887-88, p. 37). He was frequently invited to deliver public addresses, a mark of British appreciation which eventually caused him some trouble with his own government. In 1895 several speeches caused unfavorable comment, and when on Nov. 7 in an address on "Individual Freedom," before the Edinburgh Philosophical Institution, he took advantage of the occasion to assail the protective tariff as a form of state socialism responsible for a host of moral, political, and economic evils, the House of Representatives began to rumble with indignation. Threats of impeachment were made, but the offended representatives finally contented themselves with a resolution of censure Mar. 20, 1896 (Congressional Record, 54 Cong., 1 Sess., p. 3034. See also House Document 152, 54 Cong., 1 Sess.). Bayard's health began to fail while he was abroad and after his return in 1897 he took no part in affairs and seldom appeared in public. He died September 28, 1898 at Dedham, Mass.

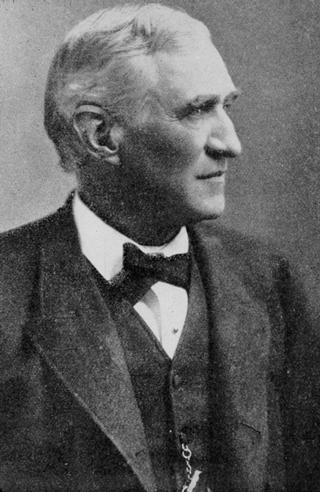

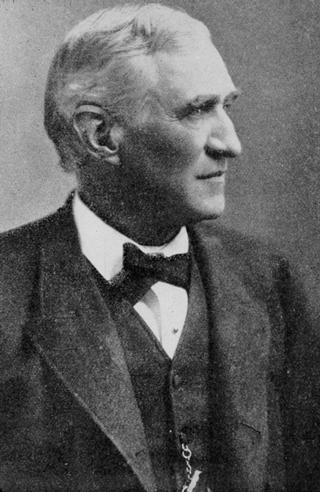

Bayard was a strikingly handsome man, over six feet in height, and of a powerful physique. His contemporaries agree that he had an unusually fine presence, and manners which Maycock describes as "dignified, courteous and prepossessing." He had, however, the convictions of an earlier day as to the responsibilities of political leadership and was never inclined, either politically or socially, to seek popularity with the country at large. He was, therefore, occasionally regarded as austere and even snobbish. As to his integrity there was no difference of opinion. He came unsmirched through a period of legislative service when ethical standards in Congress were at their nadir. John W. Foster, an opponent who severely criticized his conduct of the State Department, declares, "No man of higher ideals or of more exalted patriotism ever occupied the chair of Secretary of State" (Diplomatic Memoirs, 1909, II, 265. See also the Nation, June 17, 1897).

text by William Alexander Robinson, Dictionary of American Biography