Henry Morton Stanley

Henry Morton Stanley was born in 1841 at Denbigh, Wales, the son of a small farmer named Rowlands, who died soon after the boy's birth. His mother's maiden name was Parry. Until his adoption in America in 1859, he was known as John Rowlands. The confusion about the date of his birth, taken into consideration with the marked heartlessness of his mother and uncles toward him, has led some students of his history to suspect that he was illegitimate. He lived with his mother's father till the latter died in 1847; with him, departed the last vestige of humane treatment the child was to know. One day the son of the family with whom his uncles boarded him told him he would be taken on a journey to visit his Aunt Mary, whom he had never seen (Autobiography, p. 10). He set out happily and was delighted to see the imposing house where the cart finally stopped. He ran in looking for his aunt, to meet with mockery and taunts. The building was St. Asaph Union Workhouse. John now came under the discipline of the boys' schoolmaster, James Francis, a fanatically brutal man who ended his own days in a madhouse. Stanley has related briefly and movingly how he and a comrade stole into the room where a boy, who had been popular with all his companions, lay dead, and how one of them, presumably himself, turned down the sheet and saw the marks of the blows which had caused his death (Ibid., p. 22). His treatment by his family and the years of horror at St. Asaph are described intimately and with much detail in his Autobiography, which was written, as he indicates, out of a desire to make his nature and character comprehensible to the world which knew him in the day of his fame. At St. Asaph his only comforter was the God revealed to him in his Bible as the Divine Father and the friend of the helpless. Out of his experiences with the scriptures and with prayer grew the faith in "A God at hand and not afar off" which so strongly influenced him in later years, and which infuses his narratives of his great exploits and some of his letters.

He was about fifteen years old when, one day, he turned on the brutal master and, to his own astonishment, worsted him in the bout. Seeing the tyrant laid low by his prowess brought a rush of conflicting emotions on the boy: fears for his life mingled with the sudden proud knowledge that he had had the courage to rebel and the muscular strength to conquer. He ran away from the workhouse in May 1856 and at last, tired and hungry, reached the house of his paternal grandfather, a well-to-do farmer, who callously showed him the door. He found refuge with a cousin, a schoolmaster at Brynford, who needed the help of a pupil-teacher, for which post Stanley's earnest application to study, while at St. Asaph, had qualified him. The same curious family resentment was evident here, too, and a year later he was sent to an uncle in Liverpool. This relative was not unkind but he was very poor. Stanley worked first for a haberdasher and then for a butcher, but he saw no prospect of advance in Liverpool so he shipped as cabin boy on a vessel bound for Louisiana in 1859. He found work in New Orleans with a merchant named Henry Morton Stanley, who became deeply interested in him, and presently adopted him rather informally and gave him his name (December 1859, Autobiography, p. 120). In the fall of 1860 he was sent to a country store in Arkansas to begin his experience as a merchant. Meanwhile, the elder Stanley went to Cuba on business and died there in 1861. He had made no legal provision for his adopted son, who did not even know of his death until some years later.

In 1861 Stanley enlisted in the Dixie Grays, and in April 1862 was taken prisoner at the battle of Shiloh. He has written a vivid description of the hardships endured by those Confederate prisoners, who did not die under them, at Camp Douglas, Chicago. After two months' experience of them, he enrolled in the Federal artillery but his physical condition was so bad as to render him useless, and he was discharged within the month. He worked his way back to England and sought out his mother, who showed him plainly that, like the rest of his relatives, she wanted nothing to do with him. He returned to America in 1863, enlisted in the United States Navy the next year and was present at the attack on Fort Fisher, N. C.

Given the talent for narration and description, the habit of close observation and the thoughtful mind, it was natural that Stanley should turn to journalism, after the war, at a time when so much American territory, and so many colorful phases of American life, were still undiscovered literary material. He crossed the plains to Salt Lake City, Denver, and other western parts, sending to various newspapers accounts of his journeys which were eagerly read by the public. Apparently there was a career for him as a press correspondent. In 1866 he was in Asia Minor; the next year the Weekly Missouri Democrat of St. Louis sent him with General Hancock's army against the Indians and his reports of this expedition brought him a commission from the New York Herald to accompany the British forces against the Emperor Theodore of Abyssinia in 1868. Stanley distinguished himself by sending through the first account of the fall of Magdala. This was, in newspaper parlance, a brilliant "scoop" for the Herald. The younger James Gordon Bennett, 18411918 [q.v.], took note of the young journalist and commissioned him to travel wherever matters of dramatic interest seemed to be looming and to report on them for the Herald. In 1868 Stanley went to Crete, then in rebellion, and later to Spain, where he reported the state of affairs following on Isabella's flight and the Republican uprising (1869).

|

In response to a wire he joined Bennett in Paris in October 1869, and was informed that his next task would be to lead an expedition into the heart of Africa to find David Livingstone (Autobiography, p. 245). There had been agitation in Great Britain for some time over the probable fate of the Scotch missionary, and the general belief now was that he had perished. Bennett may have shared this opinion, while still seeing the expedition as spectacular publicity for the Herald, for he gave Stanley other assignments which delayed him en route so that he did not reach Zanzibar till Jan. 6, 1871. Newspaper enterprise of this sort was new to England: it roused a storm of fury which was to break later about Stanley's head. The Royal Geographical Society was inspired to take up the search for Livingstone, subscriptions poured in, and an expedition was launched. Meanwhile, Stanley had seen the opening of the Suez Canal, visited Philae, Jerusalem, Constantinople, and the scenes of the Crimean War, had traversed the Caucasus and crossed Persia to the sea at Abu-Shehr, sailed thence to Bombay, and from Bombay to Africa. On Mar. 21 he set off for the interior. In this wild land, wholly strange to him, he was to go through hardships and perils for which his past experiences had little prepared him, and which would test his full equipment of intelligence and moral force. But, in due course, he raised his helmet to a frail, grayhaired, white man in the native village of Ujiji, and spoke the greeting which has passed into the history of humor, as well as of exploration: "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?" The meeting occurred on Nov. 10. Livingstone's report of it is less restrained: "I am not of a demonstrative turn; as cold, indeed, as we islanders are usually reputed to be, but this disinterested kindness of Mr. Bennett, so nobly carried into effect by Mr. Stanley, was simply overwhelming. . . . Mr. Stanley has done his part with untiring energy; good judgment in the teeth of very serious obstacles" (The Last Journals of David Livingstone, 1874, vol. II, 156). Stanley had brought a tent and other comforts and necessaries for Livingstone, as well as a supply of trading goods. In company with Livingstone he explored the northern shore of Lake Tanganyika, where the discovery was made that the river Rusizi flowed into, not out of, the lake and therefore was not one of the Nile's headwaters. The discovery was of great importance at that time when the problem of the sources of the Nile was uppermost in the minds of geographers.

In 1872 Stanley was back in London, bearing Livingstone's journals and letters to his children and friends. In that year he published his account of the adventure, How I Found Livingstone. In the meantime the English expedition had come to nothing. The fury of resentment which burst upon the young explorer, from certain quarters, is difficult to understand, however much American newspaper methods may have been disliked by conservative Englishmen of that period. It was loudly asserted that Stanley was a cheat and his story a lie, that he had not found Livingstone, that he had not made the journey to Ujiji, which was a feat not possible of achievement by a young man of his total inexperience in Africa; as to Livingston's journals and letters, Stanley had forged them. Investigation brought to light these shocking facts as proofs of his fraudulence: his name was not Stanley, it was John Rowlands, and he was a "workhouse brat" from Wales. However, Livingstone's son verified his father's handwriting in the journals, the letters were declared genuine by himself and by friends who had received them; and Queen Victoria sent Stanley her thanks for the great service he had rendered, and a gold snuff box set with brilliants.

Later in the year Stanley lectured successfully in the United States; and in 1873 the Herald sent him as special correspondent with the army of Viscount Wolseley, on the Ashanti campaign. He was at the island of St. Vincent, Cape Verde Islands, on his way home next year when he heard of Livingstone's death. Stanley went on to England and sought sympathy and support for plans, which he had been formulating, to carry on Livingstone's work against slavery and to settle geographical problems which his death had left unsolved. The latter were uppermost in his mind. John Hanning Speke, discoverer of Victoria Nyanza, the second largest lake in the world, believed rightly that he had discovered the source of the Nile but his conclusions were not yet considered final by geographers. He had not explored Victoria's shores, hence the point was still unsettled whether this was one vast body of water, or one of a group of lakes. Furthermore, there was Livingstone's belief that the Lualaba, or Congo, was the upper Nile. Such an expedition required a good deal of money to back it, as well as a spirit that was not looking chiefly to journalistic profits, since its purposes were purely scientific. Stanley discussed his project with Sir Edwin Arnold, the poet, then a writer on the staff of the London Daily Telegraph, a man keenly interested in Africa. Arnold's interest, happily for Stanley, was shared by his chief, Edward Levy (later Levy-Lawson and Lord Burnham), editor of the Daily Telegraph, who persuaded Bennett to join him in raising funds for an Anglo-American exploring expedition in Africa, under Stanley's command.

Stanley sailed for Africa in October of that same year, 1874, not to return until the fall of 1877, after a journey which was outstanding in its discoveries, and was to prove momentous in its commercial and political results. In short, on this exploration Stanley had accomplished more than had any other single expedition in Africa. From Jan. 17, 1875, to Apr. 7, 1876, he had been engaged in tracing the extreme southern sources of the Nile from the marshy plains and uplands, where they rise, down to the immense reservoir of Victoria Nyanza. He had circumnavigated Victoria's entire expanse, explored its bays and creeks by boat and, on foot, had traveled hundreds of miles along its northern shore, discovered Albert Edward Nyanza, and also explored the territory between Victoria and Edward. By proving that mighty Victoria was one single lake and not five, he ensured to Speke, its discoverer, "the full glory of having discovered the largest inland sea on the continent of Africa" (Through the Dark Continent, 1878, vol. I, 482).

|

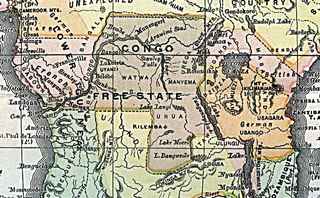

After his exploration of the Nile's headwaters, Stanley made as complete a survey of Lake Tanganyika and then turned his attention to the Congo. From Zanzibar he reached the Congo at Nyangwe, the place of Livingstone's death, and there launched upon the unknown stream of the second largest river in the world. He forced his way through the territory where Arab hostility had turned Livingstone back, and followed the long course of the river to its sea mouth at Boma, where he arrived in August 1877. The journey was one of terrible hardship owing to natural obstacles, fever, and unfriendly natives. Stanley's three white companions died in the jungle; his own powerful constitution was sapped, his face lined, and his hair nearly white, when he again reached civilization. The next year, 1878, he published Through the Dark Continent (2 vols.) His talent for the apt phrase gave Africa what amounted to a new name, for "Dark Continent" caught the imagination of scientists as well as of press writers and the general public. While the solution of geographical problems was of immense value, Stanley's journey resulted significantly in other ways. From Uganda he sent letters to England emphasizing the importance of sending missionaries to the court of Mtesa; and the immediate response was the first step in bringing the territory of the Nile's headwaters under British protection. During his stay with Livingstone, Stanley had adopted the missionary's recent conviction, namely, that it was impracticable to Christianize natives who were utterly at the mercy of the Arab slave traders, and never free from fear of raids. Protection in some form must be established first, and the cruel trade abolished, before the gospel could be preached. Also the new region which Stanley had traversed held immense commercial possibilities in its rubber and ivory; to open it up to commerce and civilization needed only swift-moving and stubborn enterprise. It was the American Stanley, the man who had seen the wheel-ruts of pioneer wagons on the western prairie and young sturdy towns on the recent Indian battle-grounds, who looked at the Congo region and saw nothing there to daunt determined men thoroughly equipped with the means and methods of civilization.

His news reached Europe ahead of him, and Leopold II of Belgium caught the vision, in its commercial hues at least; his commissioners were at Marseilles when Stanley's ship docked, with proposals that he return to the Congo in Belgian employ. Stanley refused and continued his journey home. He was worn out and needed to recuperate and also he wished Great Britain, not some other power, to make use of his discoveries. To his great disappointment British interest was not aroused. In November 1878, at Leopold's repeated request, Stanley went to Brussels and agreed to lead an expedition for study of the region which he had discovered. He arrived on the river in August 1879. He remained for five years and established twenty-two stations on the Congo and its tributaries, put four small steamers on the upper river, and built a road past the long cataract of Stanley Falls. The natives, watching the arduous work of road-building go forward under the inflexible will of the white man, gave him a name meaning the strong one, the rock-breaker--"Bula Matari." It is carved on the rough stone pillar which marks his grave. On the basis of Stanley's work the Congo Free State was formed. In 1885 Stanley published his book, The Congo and the Founding of Its Free State (2 vols.). During the Berlin Conference of 1884-85, which dealt with African affairs, he acted as technical adviser to the American delegates. He lectured in several German cities, where he found the people much more interested in Africa than were the English, who remained curiously indifferent to the vast interests at stake--or, perhaps, blindly and stubbornly resentful against the "American journalist," still an American citizen, who trod on their traditions of good form and modesty and always finished successfully whatever enormous task he set himself. He was "Bula Matari" in a symbolic sense long before a group of wondering blacks so christened the first road-builder in their forest.

In 1887 Stanley sailed for Africa again on a three-fold mission. He was to further plans for the establishment of a British protectorate in East Equatorial Africa; to give help to the Congo Free State, which was seriously menaced by Tippu Tib and his Arab tribesmen from Zanzibar; and to proceed to the relief of Emin Pasha, governor of the Equatorial Province of Egypt, who was cut off after the fall of Khartoum (1885) by the fanatical force of the Mahdi. As to its outlined purposes, the expedition proved somewhat abortive. Seeing the strength of the wily Tippu Tib, Stanley resorted to the bold expedient of creating him governor of Stanley Falls station for the Congo Free State and then arranged with him for carriers on the march to relieve Emin, who, as it turned out, did not wish to be relieved, nor to abandon his province, and who felt that Stanley's arrival had caused him to lose face with his people. In achieving this unsatisfactory result Stanley crossed the densest area of the Ituri, or Great Congo, Forest three times. The expedition crawled at a snail's pace, covering only three or four hundred yards in an hour, among densely packed trees which rose a hundred and fifty feet with interlaced branches hung with vines that shut out the sun's rays. Underbrush twice a man's height clogged the path, which lay over swampy ground, the breeding place of innumerable insects and of fever. Stanley nearly died of fever himself and he brought out of the forest only a third of the men he took in with him. This adventure, with descriptions of the forest and its animal life, as well as both vivid and valuable ethnological data regarding the Pigmy tribes, forms the content of In Darkest Africa (2 vols.), which was published in 1890 in six languages. On his way from the vast shadow where so many of his men had met death Stanley discovered the Ruwenzori or "Mountains of the Moon." He also traced the Semliki River to its source in Albert Edward Nyanza.

He was greeted warmly in England. Among numerous honors he received the degree of D.C.L. from Oxford and of LL.D. from Cambridge and from Edinburgh. He was then about fifty years of age. On July 12, 1890, he married Dorothy, second daughter of Charles Tennant, at one time member of Parliament from St. Albans. He spent two years lecturing in Australia and New Zealand and in America, where he revisited the scenes of his youth. His roving career had been a long one and his African journeys had taken toll of his vitality, but his mind was as restless and eager as ever. Chiefly to provide an outlet for his mental energies, his wife persuaded him to run for Parliament as the Liberal-Unionist candidate for North Lambeth in 1892, after his renaturalization as a British subject in 1892; he was defeated by a small majority. In the next election, 1895, he was successful; but representing an English constituency failed to interest the former Congo State builder, and he did not campaign again in 1900. The year of his election he published My Early Travels and Adventures in America and Asia (2 vols., 1895). In 1897 Stanley went on his last journey to Africa, as the guest of the British South Africa Company, to speak at the opening of the railway from the Cape to Bulawayo. In his last volume, Through South Africa (1898), he described his tour to the Victoria Falls of the Zambezi, and enriched the gallery of vivid portraits which his books present with a lifelike and penetrating study of Paul Kruger. In 1899 he was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Bath. His health was failing and he retired to his small country estate called "Furze Hill," near Pirbright. He died on May 10, 1904, at his London house in Richmond Terrace, Whitehall, after a paralytic stroke. Services for him were held in Westminster Abbey, although the Dean refused him a resting place there. He was buried at Pirbright. He left one son, Denzil, apparently adopted. Three years later his widow married Henry Curtis, F.R.C.S.

Africa 2001 bg from CIA

Africa 2001 bg from CIA

|

Central Africa 2001 bg from CIA

Central Africa 2001 bg from CIA

|

The extent of his geographical discoveries alone places Stanley's name first among African explorers, even when one considers the great contribution made by Livingstone during his many years in Africa. In addition to his qualities as an explorer, Stanley possessed the vision and organizing ability of the true pioneer builder. He believed wholly in the superiority of his race and civilization; and, as organizer of the Congo Free State (Belgian Congo), never doubted that he was bringing good to the natives. He saw himself pushing on Livingstone's work and adding to it the benefits of a vast commerce. As a westerner he looked at the Congo and, as a westerner, he sped on to the tasks of Bula Matari in Leopold's employ when the British rejected the empire in embryo which he offered them. His disappointment over later developments in the Congo is suggested by his phrase, "a moral malaria." Moral force was strong in him. It was rooted deeply in his faith in God; and, in resisting the common vices to which he was early subjected, it was aided by his innate fastidiousness. In his teens he thought drunkenness and licentiousness both repulsive and stupid, and he never changed this opinion. His strong will was invoked not only to overcome external obstacles but, less happily, to suppress his naturally affectionate and trusting temperament and all desire for affection from others. Though he had to fight his way through hostile regions, at times, in Africa, he was generally successful in winning the friendship of the natives. But in civilized countries he had no tact. Self-schooled to live without illusions and emotional expression, he never understood the offended clamor aroused by his criticisms of the methods of other men in Africa who had perished and become heroes. He himself did not think that mistakes detracted from these men's personal nobility, and he believed that their errors should be seen and avoided by their successors; but the public called him a brute. To say that he was egotistical and ambitious is to state the obvious: his loneliness made him introspective and self-absorbed; and his energy and pride drove him on to win a fame that should wipe out the stigma of his despised origin. His total lack of humor possibly has been overstressed; it is a question whether humor develops later in any one whose youth has been without laughter. Three tragic episodes of his younger life were continuously with him: the day he entered St. Asaph's, his mother's cold dismissal of him years later when he sought her out, and the treatment he received in England on his return from finding Livingstone. Harsh and narrow in his judgments of those who wronged him, he forgave nothing and his wounds were always fresh. A Welsh writer has said of his countrymen that they are "narrow, but dangerously deep," and Stanley was Welsh. His unfinished Autobiography, begun chiefly in the desire to make his character understood, shows him still bewildered by the chicaneries and cruelties he relates. He was preŽminently the man of action, ever on the move from one exacting labor to another, yet there was a metaphysical cast to his mind that probed for answers beyond the actualities of his life and career. It may have shaped his last conscious thought. As the watchers by his bed heard Big Ben strike, Stanley opened his eyes and said, "How strange!--So that is time." He died two hours afterwards. - text by Constance Lindsay Skinner, Dictionary of American Biography

Reasons for Empire

map list