Glory's Historical Context

Morris Island

Morris Island

|

Glory tells the story of the creation of the Massachusetts 54th Colored Regiment and its attack on Fort Wagner near Charleston, South Carolina, July 18, 1864. It begins with Robert Gould Shaw (played by Matthew Broderick, who claimed to be a distant relative of the real Shaw) writing a letter to his mother in Boston. He has just been promoted to Captain (although one marching scene shows him wearing no insignia within his epaulets as would a second lieutenant). He is about to go into battle at Antietam on Sept. 17, 1862, the bloodiest day in American history with a total of 22,000 casualties including 6600 dead. Shaw is one of these casualties, but is discovered wounded by grave-digger Rawlins (Morgan Freeman). He recovers and returns home, decides to accept command of the new black regiment. At the Readeville Camp, Mass., in November 18, 1862, the four central black characters meet as tent-mates: Sharts is a fieldhand from South Carolina who stutters (Jihmi Kennedy), Trip is a militant runaway from Tennessee (Denzel Washington), Rawlins is the grave-digger runaway (Morgan Freeman), and Thomas is the educated freeman from Boston (Andre Braugher). The Army is a transforming experience for the men who are unified despite class and character differences. The regiment is sent to Beaufort, South Carolina, June 9, 1863, where they encounter missionaries from New England who are teaching contrabands, and Edward Pierce (Christian Baskous) who writes for Harpers Weekly. They see "Morse's Photographs" and the red-pants brigade of colored soldiers commanded by the jayhawker Col. Montgomery (Cliff De Young). Shaw reluctantly helps Montgomery burn a "se-cesh" town. The regiment sees its first military action 2 days before the climactic charge against Fort Wagner on James Island. The film ends with Shaw's body buried with his fallen men.

Robert Gould Shaw

Robert Gould Shaw

|

The Massachusetts 54th was not the first colored regiment. In April 1862 Secretary of War Edwin Stanton approved a request from David Hunter to allow blacks to be used a garrison soldiers in the occupied coastal areas of Cape Hatteras. Hunter did not seek volunteers but rounded up former slaves by force and issued them Zouave uniforms to form the 1st South Carolina Colored Regiment. The Boston lawyer and missionary Edward Pierce wrote critical articles for the northern press about the "sorry tale" Hunter's regiment. On May 19, Shaw wrote his father from Washington DC that he wanted to command a colored regiment, but instead he would be sent to Antietam. The Second Confiscation Act of July 17, 1862, allowed the arming of blacks and the Militia Act authorized payment to black soldiers of $3 below the pay of white soldiers, but Lincoln refused to exercise this authority. However, Union commanders did so on their own authority. Ben Butler formed the 1st Louisiana Native Guards Sept. 27, 1862. Jim Lane in Kansas formed the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteers in September and they fought the first military engagement by black soldiers at Butler, Missouri, in October. Thomas Wentworth Higginson formed the 1st South Carolina Colored Volunteers Jan. 31, 1863, at Port Royal. Col. James Montgomery of Kansas was a friend of Lane and formed the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers in January 1863. Butler's three Louisiana Guard units, with Higginson's and Lane's and Montgomery's regiments, became the first six federal colored regiments by January 1863. On Feb. 5, Shaw wrote his father that he had decided to accept the offer of Gov. Andrew to command a colored regiment. On Feb. 15, a newspaper advertisement in Boston called for "volunteers of African descent" to join the new 54th regiment for a bounty of $100 and monthly pay of $13. Shaw was in Boston at this time and already had received his command when he is shown with Gov. Andrew and Frederick Douglass (but Douglass was 45 years old, not the elderly figure portrayed in the film). On May 13, Congress created the Bureau of Colored Troops that would ultimately organize 166 colored regiments with 179,000 blacks in uniform, in addition to the 10,000 blacks serving in the Union Navy.

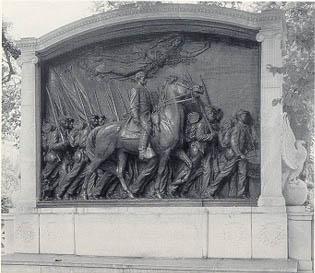

Memorial in Boston Common

Memorial in Boston Common

|

The Massachusetts 54th and 55th regiments would be separate from the BCT regiments, due to the fact that they were formed before the May 13, 1863, authorization and were supported by the abolitionists in Boston. These regiments would be composed mostly of literate free blacks, such as two sons of Frederick Douglass. The four central characters in the film are fictional (as also are the characters of Forbes and Sgt. Mulcahy) and misrepresent the composition of the 54th as made up of former slaves, not northern freemen. The 54th would succeed in protesting the pay inequality of black soldiers and cause Congress to raise the monthly pay to $13 (due to Shaw's efforts, not the fictional Trip). It would also succeed in allowing blacks to be promoted to command officer ranks. The 54th arrived at Beaufort June 3, 1863, participated in the burning of Darien, Georgia, June 11. The regiment arrived at James Island July 16, one day after the draft riots in New York City had begun. These riots were caused by Irish opposition to the draft and to blacks whom the Irish feared would become free and take their jobs. Robert Simmons was a sergeant in the 54th who lost a nephew to the mob in New York, and would himself be killed at Fort Wagner. Lincoln at this time was also being attacked by Northern Democrats for his emancipation policy and the growing power of the Republican administration to raise black troops and draft white troops. General Ulysses S. Grant had recently endorsed the use of black soldiers and Lincoln was looking for evidence to support his policies. However, none of this national context, nor the story of Sgt Simmons, is in the film.

The 54th was transferred to Morris Island July 16 where Shaw volunteered his regiment to Gen. Strong for the attack July 18 on Fort Wagner. The charge was northward along the beach toward the fort (not with the rubber bayonets used in the film, and not the southward direction caused by the location of the set built on a Georgia beach for the film). Shaw and 3 other white officers were killed, 277 soldiers killed and 146 wounded. The bravery of the black soldiers of the 54th, the tragic death of Robert Shaw, the eyewitnesses such as Clara Barton and Harriet Tubman, and the national context of the debate over emancipation made the charge at Fort Wagner nationally famous. It did not cause Congress to authorize more black soldiers because that had already been done May 13. It was not the end of the 54th because the regiment went on to fight battles at Olustee in Florida in Feb. 1864 and at Honey Hill in South Carolina.

Memorial in Boston Common

Memorial in Boston Common

|

Kevin Jarre was inspired to write the screenplay because he noticed the bronze monument to the 54th in Boston Common included the faces of black soldiers and he wanted to tell their story. Augustus Saint-Gaudens was commissioned in 1882 to sculpt the memorial and he used black citizens of New York and Boston as his models for the faces of the black soldiers. When the bronze was dedicated in Boston Common 1897, it was a symbol of "the New England Way, a moral absolute" according to Lewis Simpson, that was destroyed by the Civil War along with slavery. Robert Gould Shaw was an example of New England superiority, the intellectual and moral leadership that created a culture of the mind, and the necessity to destroy the mindless South, to emancipate America from historical reality to achieve an idealization of progress. However, the inward cultures of New England and the South were both destroyed in the Civil war that instead gave birth to Lincoln's "a new nation."

Saint-Gaudens

History Department | Filmnotes | revised 3/7/06 by Schoenherr