Margaret Bourke-White has been portrayed as one of the leaders of women

in the photojournalist field. Born to Joseph White and Minnie Bourke on

June 14, 1904 in Bronx, New York, never thinking that photography

would be her way of life. She went to college with her mind set in a degree

in herpetology, and graduated in 1927 from Cornell University. Her interest

in photography came while taking a class that led to a hobby, this in turn

would lead her to a job that would transform it for all photographers to

come.

Margaret Bourke-White has been portrayed as one of the leaders of women

in the photojournalist field. Born to Joseph White and Minnie Bourke on

June 14, 1904 in Bronx, New York, never thinking that photography

would be her way of life. She went to college with her mind set in a degree

in herpetology, and graduated in 1927 from Cornell University. Her interest

in photography came while taking a class that led to a hobby, this in turn

would lead her to a job that would transform it for all photographers to

come.

Margaret Bourke-White started out taking a photography class and her fathers interest to fuel this talent. She began as an industrial photographer in Cleveland, Ohio, for the Otis Steel Company in 1927. She was the first photographer in 1929, for Fortune magazine. This paved the way for her to be hired as the first Western photographer given permission to enter the Soviet Union. With all this experience behind her, she was given the position of the first female photojournalist of Life, in 1935. Given the opportunity to experience World War II, she was one of the first females to enter a combat zone and enter and document the death camps.

Her professional career included 6 books about her travels within the United States and abroad that was with the help of her husband whom she married in 1939, but would come to divorce in 1942. She died on August 27, 1971 in Connecticut, leaving behind a legacy of photographs.

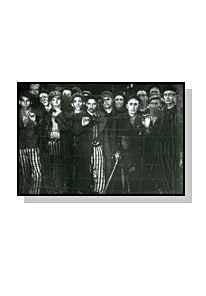

I saw and photographed the piles of naked, lifeless bodies, the human skeletons in furnaces, the living skeletons who would die the next day... and tattooed skin for lampshades. Using the camera was almost a relief. It interposed a slight barrier between myself and the horror in front of me." This was White’s response to her entrance into Buchenwald concentration camp in 1945. She had the opportunity to enter the camp with General Patton and his third army, and this was her only way of dealing with the horrific sights. This picture has become a photographic symbol of the camp life, leaving the viewer with the feeling of separation and emptiness. The picture was published in Life , on May 7, 1945, even though the camp had been liberated months before. It allowed the world to see the life many had to endure during the war years. It was considered one of the ten most iconic images of photojournalism because it informed “the world about the true nature of the Holocaust” by Time in 1989.

The picture depicts males hidden behind the wires, that had imprisoned them for years; yet these faces will not be forgotten. Pictures like this are used as tools of what life was like for them and glorifies the idea of art behind such scenes. These men were not staged or made scroungy. This was life, a life worth not forgetting. The picture has been used in countless retrospect’s of the Holocaust and Life’s special editions of photojournalism. It was considered to be use on the FDR memorial in the 1970’s, because of his presidency during the war years. It is seen in their faces that they hold the real story of what happened behind the wires, and we on the other side only can see it for its face value.